One type of archaeogaming research is digital excavation, a technical examination of the code and techniques used in old games' implementation. Video game archaeologists are digging into the code of early video games to uncover long forgotten secrets that could help modern programmers solve some of their problems today.

Since many early games on different platforms were designed with mazes, the maze game is one of the most fruitful research fields in game history archaeology. In the Atari era, game design had to be of incredible skills, because the computer systems that support game operation were very limited. Among them, mazes in Entombed has attracted researchers' interest. John Aycock of the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada, and Tara Copplestone, a researcher at the University of York in the UK, have taken Entombed as one of their research themes. John Aycock says Entombed is always fascinating. It hasn't been analyzed in depth before because it's so obscure.

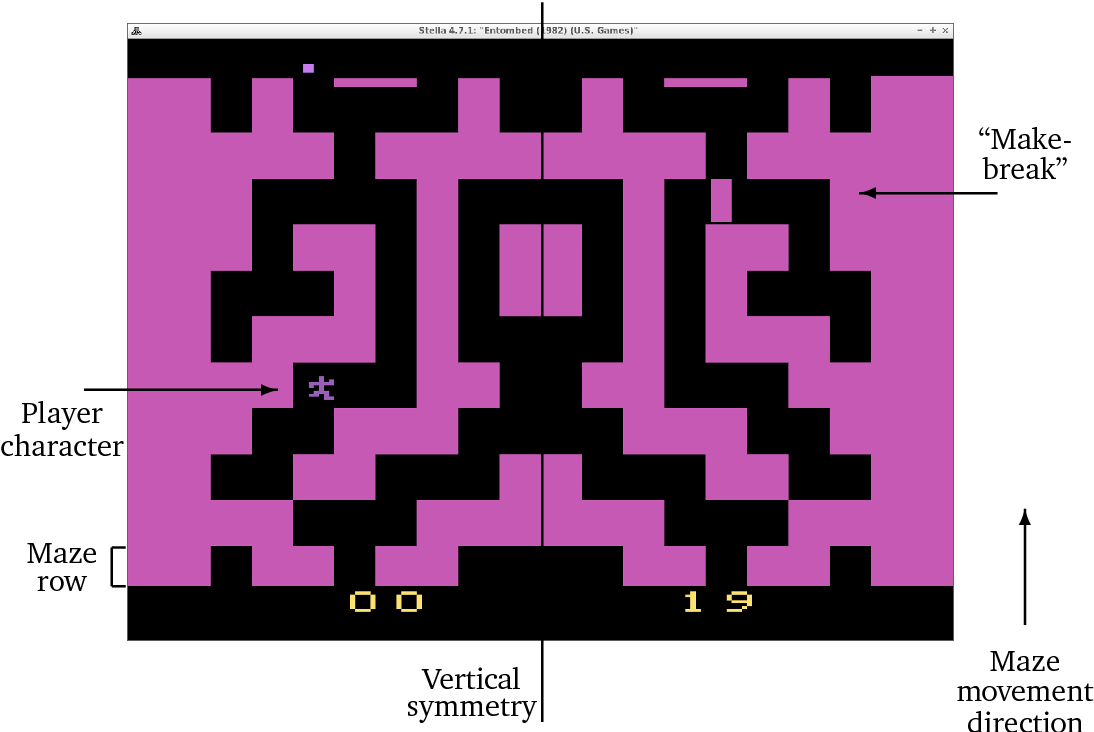

Released by U.S. games in 1982, Entombed is an Atari 2600 game designed by Tom Sloper and written by Steven Sidley. In Entombed, players need to move down through a horizontal, symmetrical, vertical and continuous rolling maze, try to avoid moving enemies on the screen, and go as far as possible; if players bump into the monsters, they will die and the game is over. The maze will continue to roll up the screen, which may cause players to fall into a dead end for they can move in any direction; if the players’ position scrolls off the screen, also the game is over.

The maze in Entombed is particularly interesting. Its design is limited by the hardware platform, but it must be efficiently generated in the game and almost does not occupy memory. Aycock and Copplestone reverse engineered and reconstructed the key areas of the code of Entombed, hoping to find its unique maze generation algorithm. They found some mysterious codes that couldn't be explained. It seems that the logic behind Entombed has disappeared forever.

Blocky two-dimensional mazes look simple by today's computer graphics standards. While in 1982, game developers couldn't just design a set of mazes to store them in the game and display them on the screen due to the platform. In many cases, the game creates a maze randomly in progress, so players never actually cross the same maze twice. "When I study this maze algorithm, it's clear that its maze algorithm is unique to this maze game," John Aycock told the BBC.

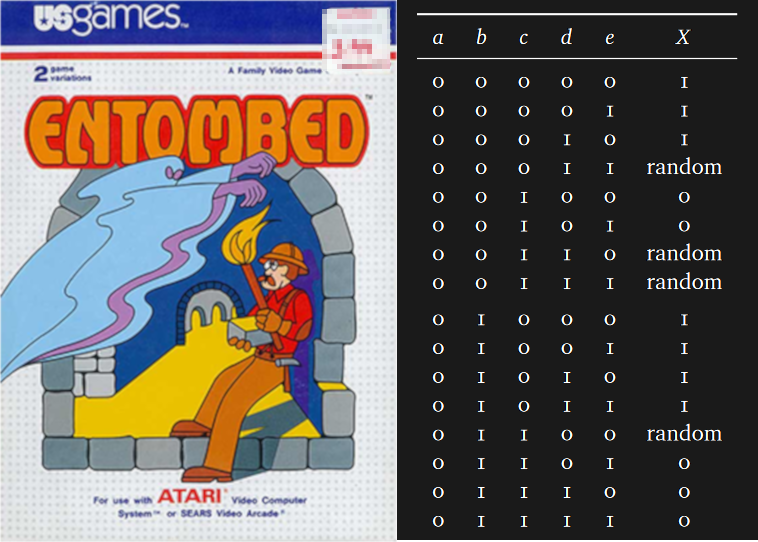

It turns out that mazes are generated in order. The game needs to decide whether to draw walls or leave space for the character to move when creating each new square of the maze, so each square should be "wall" or "no wall" ("1" or "0"). The algorithm of the game is determined automatically by analyzing a part of the maze. This logic doesn't seem complicated, but the truth is that no one really knows how to make the table of value in the game. Aycock and Copplestone tried to find the design model in the numerical value, but it didn't help. If the numerical value is completely random, the maze may appear to be unable to pass. But every time, Entombed can generate a reliable navigation maze.

During the course of the research, Aycock and Copplestone had the opportunity to interview Steve Sidley, a developer who had participated in game production. Steve Sidley could only remember that he was confused by the algorithm. He recalled that the basic maze generation program was written by a talented person who had left his job. At that time, he tried to understand the algorithm principle of maze generation, but the programmer told him that this was thought of when he was drunk and his brain was all blank. “I compiled the program overnight before coma, but now I can't remember how the algorithm finally worked.” Aycock tried to contact the special programmer, but didn't get a response. Maybe no one really understands the logic of the algorithm.

Andrew Reinhard of the University of York is also a researcher who wrote about and practiced video game archaeology. He thinks Aycock and Copplestone's work on Entombed is another hint that there are still many "gems" waiting to be discovered in old games and old software. The idea that video games from decades ago will appeal to digital archaeologists may sound strange to some people, but Reinhard points out that video games have become a major business enterprise and an important part of our culture, with game artifacts storing human history.